A Taste of Milk & Honey

IT IS INTERESTING TO OBSERVE, even in small children, the early signs of leadership ability. Of course, I am not referring to that bullying, pushing, shoving, “I must get my own way” behavior that, unless modified, carries over into adulthood. In adults it may be disguised, but it remains insecurity getting its own way, no longer pushing, and shoving but now manipulating. Rather, I am referring to that “If we form a line, we will all eat sooner” or “Why don’t we sit in a circle so we can all see?” leadership.

The quality of leadership not only appears early but it also is not necessarily joined to money or status or appearance. For example, a much beloved member of the community dies. All are in mourning and wringing their hands, but one sees that the lawn is mowed, pets are cared for, cars and drivers stand ready to meet planes, and a healthy meal is warmed. And the rest of us, no less sincere, are bringing in banana puddings, 37 of them. “If I had only known you were bringing one … “

When I taught in Oklahoma, I was a passenger on a train going from Kansas City to Oklahoma City. I was to exit at Perry, and I did, as did 90 other people. Due to heavy snowfall, the engine derailed in Perry. No one was hurt, but the announcement, “We will be here at least two days” was painful enough. Anger, crying, confusion, frustration, threats of lawsuits abounded, but in less than three hours, order prevailed. We were in an American Legion building, cots were coming in from the National Guard, refreshments with the promise of meals later came from churches, phones were provided.

How so? A cowboy was on the train, along with his horse. He rode his horse into the building and from the saddle he explained to us our behavior for the next two days: cots for those under eight, and those over 65 would be nearest the two restrooms; these two groups would be first in the food lines; a sign-up sheet would be near each of the four phones, no calls over five minutes, etc., etc., etc. None of us complained. Who was our leader? A rodeo cowboy. He had a gift for leadership.

At least “gift” is what the Apostle Paul called it, a “gift of leadership.” In the church, he said there are gifts of healing, of teaching, of preaching, but also of leadership. Thank goodness!

While observing the children, I am encouraged. I hope they will not be deterred by adults who have the positions of leadership but not the gift.

From Dr. Craddock, Milk & Honey, October 2011

From the Executive Director

As a part of fulfilling the ‘Family Enrichment’ part of our mission, The Craddock Center joined with the Fannin County Family Connection, Fannin County DFCS, Fannin County Public Library, Highland Rivers Health, North Georgia Autism Foundation, and the North Georgia Mountain Crisis Network to start the Fannin County Mental Health Awareness Campaign. We started a program called ‘Mental Health Matters, It’s Okay to Not be Okay.’ As a part of this initiative, we had a six-part series on a local TV channel focusing on various aspects of mental health and worked with local governments to Proclaim Mental Health Awareness months. Our current initiative began on January 26, 2022. The Fannin County News Observer newspaper agreed to an article focusing on a mental health topic the last week of the month for the 12 months of 2022. The Craddock Center is noted at the end of each article as part of the collaborative spearheading this initiative. David Ralston, the Georgia Speaker of the House, provided an article in January to kick off the series. The Craddock Center will have its article in the paper on October 26th. November is National Family Literacy month, and our article will focus on the impact of mental health issues on childhood literacy.

The following article from The Craddock Center will appear in the Fannin County News-Observer newspaper on October 26th as part of a monthly series….’Your Mental Health Matters: It’s Okay not to be Okay’

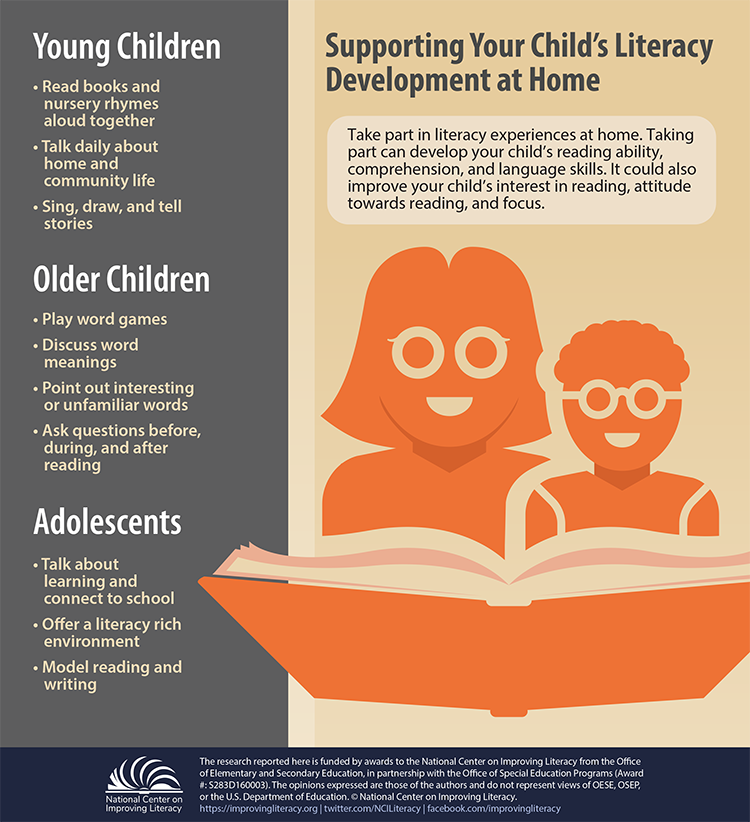

National Family Literacy Month, which takes place in November, is an opportunity for families to learn and read together. It also celebrates the work that literacy programs, such as The Craddock Center, do to empower families in our communities.

What can the family do together to celebrate? Read, read, and read some more. Read about anything and everything that interests your children. No matter what it may be, read for the enjoyment of reading. Discuss what you’ve read. Encourage your children to talk about what they have read. Whenever we experience something good, we talk about it. Talk about the books that excite you with your children. Ask your child “what would happen if?” questions, encourage writing and drawing about books, play word games, and teach your child rhymes and songs. Visit your local library as a family. In addition to books, find out about all the programming your library has to offer. You’d be surprised that many offer classes, workshops, movie nights, reading groups, and more for all ages on a vast variety of topics.

School is not the only place childhood literacy skills develop. Children’s literacy is also impacted positively and potentially negatively by what happens (or doesn’t happen) at home and with the parents, grandparents, and siblings.

A major negative impact to literacy that occurs in the home are mental health issues and dealing with the pandemic the last two years has certainly exacerbated the impact. Many researchers are reporting an increase in anxiety, depression, loneliness, and families feeling traumatized as a result of the pandemic.

What if the child has mental health issues?

Effects of the coronavirus crisis linger as 220,000 kids in Georgia report that they struggle with anxiety or depression, according to The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Mental health challenges can be a barrier to learning and can negatively affect students’ social and emotional development and well-being into adulthood. Children with mental health disorders are more likely to be unhappy at school, be absent, or be suspended or expelled. Their learning is negatively impacted because of poor concentration, distractibility, inability to retain information, poor peer relationships, and aggressive behavior. They also may be withdrawn and difficult to engage.

A recent survey of First Book’s Network revealed that most educators believe the pandemic has introduced new mental health challenges among students – making this already significant issue even more pressing.

First Book educators share the following concerns about students’ mental health and well-being:

- 98% of educators say mental health challenges act as a barrier to children’s education.

- On average, educators report that over half (53%) of their students struggle with mental health.

- 72% of educators say the pandemic has introduced new mental health challenges among their students.

- 65% of educators believe class/income is the most relevant social factor that impacts children’s mental health.

Opening up and talking with a child about their mental struggles can help reduce the seemingly powerful influence those struggles have on their life. If you think a child is struggling, it can be helpful to allow them to trust you and open up to you. For instance, they can speak to a trusted parent, family member, friend, religious leader, mental health therapist, or health care provider.

What if the child has parents or siblings with mental health issues?

School children with family members with mental health issues are often negatively impacted. Impacts are often seen with school performance and social behavior in the school setting. Teachers are then required to support children in coping with their home situation and their education needs.

Although “burdens” in the family are perceived as major influences on children’s school day and performance, teachers report that they do not feel sufficiently prepared for supporting and coping with the family challenges of affected students. Recognizing the family situation of children with mentally ill family members can be especially difficult for teachers. Responding inadequately to the needs of affected children was perceived as a serious burden for teachers themselves.

These “burdens”, related to mental health issues, are also likely to impact the learning and socialization that needs to take place at home. Is the child being read to? Receiving the necessary positive interaction and socialization from their family members? Do they have an adult they can trust to take care of their needs?

If you, your family, or someone you know needs help

If you or someone you know is struggling, you are not alone. There are many support services, and treatment options that may help. Call the NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) helpline at 800-950-6264. In a crisis, text ‘NAMI’ to ‘741741’ for 24/7 confidential, free crisis counseling. NAMI is the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization dedicated to building better lives for the millions of Americans affected by mental illness. NAMI has started a Family Support Group in Fannin County and is free to participants. It meets the 4th Monday of each month from 5:30 to 7:00 pm. For more information or to register, please contact Martha at marthaheffner2@gmail.com .

Also, ‘9-8-8 in Georgia’ began July 16, 2022. 988 is an alternative to 911 when you are in a mental health or behavioral health crisis. You will be connected to a trained clinician, rather than law enforcement.

In addition, the Georgia Crisis and Access Line (GCAL) continues to be available to Georgians 24/7/365. Their number is 1-800-715-4225.

Thank You Arts Specialists!!

The primary role of the Arts Specialists is to love children and to engage and enrich them through music and movement. They are the key to the success of the Children’s Enrichment Program. Using Songs and Stories, the Arts Specialists conduct 30-minute programs with preschoolers according to a defined weekly schedule. They use music, instruments, props, movement, puppets, storytelling, and routines to encourage children to sing, move, dance, and play. They help build vocabulary and self-esteem and promote motor and rhythmic skills. They serve as cheerful “ambassadors” of The Craddock Center at all the schools we serve. Our Arts Specialists serve approximately 1,110 pre-K and Head Start students in 61 classrooms in 22 schools in three states! Sincere and heartfelt thanks to Natalie Jones, Tracy Walker, Jane Cunningham, Claudia Bradford, Sheila Clayton, and Kathy Thompson!

The Children’s Enrichment Program is considered the signature program of The Craddock Center. Our program is delivered free of charge to schools and Head Start programs in our Southern Appalachian area. Priority is given to schools with the highest percentage of children on free or reduced lunches. We have specially designed our programs, based on research for optimal learning to best prepare these children for Kindergarten. The Craddock Center’s programming becomes the foundation for these children to achieve their full potential in all areas of their lives.

Cub Scout Pack Hosts BBQ Fundraiser

On March 26th of this year, our Cub Scout Pack held its first Pinewood Derby. The Pinewood Derby is a Cub Scout car race where 7-inch toy cars, weighing no more than five ounces, are raced down a sloped track. The concept originated with Don Murphy in 1953. Murphy noted, “I wanted to devise a wholesome, constructive activity that would foster a closer father-son relationship and promote craftsmanship and good sportsmanship through competition.”

Scheduling the event was an issue because our Pack did not have its own track. They had to borrow one from another Pack which made nailing down a date difficult.

The Craddock Center stepped up with a challenge…we will pay 50% of the cost of the track if you raise the remaining funds.

Our Pack stepped up and sought out an organization to help. The Georgia High Country Builders Association held a BBQ fundraiser event on July 9th of this year. The event raised the 50% needed for our Pack and The Craddock Center donated the remaining $700 to ensure our pack could purchase its own track for future Pinewood Derby events.

Remembering Helen Lewis

On Friday, March 4, 2005, The Craddock Center hosted the first Helen Lewis Lecture. This was a way to honor and recognize a national treasure for her lifetime of teaching, organizing, and working with Appalachian communities so they could help themselves.

Helen passed away on September 4, 2022, following complications from COVID. Her obituary is shared for you below.

‘Helen Matthews Lewis died Sunday, September 4, 2022, in Abingdon, Virginia, of complications following COVID. She was born October 2, 1924, in Nicholson, Georgia, oldest child of Hugh and Maurie Harris Matthews. She is survived by her sister’s children and grandchildren.

Helen spent a lifetime as a radical educator and activist, working for justice from the Deep South to Appalachia and internationally. Helen taught in colleges and prisons; went to jail for civil rights and stood on picket lines; planted gardens and wrote poetry. In all her work she connected, supported, and pushed people to work together and go a little farther to build communities and make change.

After attending Bessie Tift College, Helen graduated in 1946 from Georgia State College for Women in Milledgeville. She received a Master of Arts degree from the University of Virginia in 1949 and a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky in 1970. She received honorary doctorates from Berea College and Wake Forest University.

Much of her life was spent in education, both formal and informal. She came to Southwest Virginia in 1955 to work at Clinch Valley College (now the University of Virginia’s College at Wise). There she learned from and with her students about experiences of miners and their families. Through her speeches, community work, and numerous publications, she pioneered new interpretations of Appalachia’s history and resource exploitation that reexamined Appalachia’s role in the global economy. She taught many years at Clinch Valley College, and at East Tennessee State University, Berea College, and Appalachian State University.

Through her work at Highlander Research and Education Center she led community-based education projects in Dungannon and Ivanhoe, Virginia, and McDowell County, West Virginia; worked to build connections between mining communities in Appalachia and Wales; and worked with community educators in Nicaragua, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Working with Appalshop, she led in the production of films on the history of Appalachia. She served as President of the Appalachian Studies Association, and that organization created the Helen Lewis Community Service Award in her honor. Her pioneering work in mountain communities led her to be known as “the grandmother of Appalachian studies.”

Helen lived in a number of places across Appalachia, including Wise and Dungannon in Virginia, New Market, Tennessee, Berea, Kentucky, and Blue Ridge, Georgia. For the last years of her life, she lived in the ElderSpirit community in Abingdon, Virginia. In all these places she created a warm, welcoming home where she shared fellowship and remarkable cooking. In her later years she turned to poetry and ministry, the latter informed by her lifelong understanding that “faith without works is dead.” Her life of organizing and educating, of nurturing growth in gardens and in communities, of taking care and laboring for the long arc of justice, leaves behind an interwoven network of people who loved her, admired her, and will carry on her work.’